Why Do We Need Type Theories?

With data-driven trait theories like the Five Factor Model dominating scientific research, people may wonder what use there is for type theories that posit there are distinct types of personality. This article looks as the benefits of such an approach.

Reason 1: Type theories enable tailored insights

In psychology, coaching, and therapy there are two main ideas on how to treat a client:

The first view treats everyone as inherently the same, with the same inherent desires and needs. An example of this can be seen with Maslow's hierarchy of needs, where everyone is posited as existing somewhere on the same hierarchy, and needing the same things in the same order. Inevitably, such theories rely on significant projection on the account of the expert onto the client. This first view is only satisfying to a client insofar as they are representative of the 'universal person' that the theory describes. If the client don't have the same priorities as seen in Maslow's hierarchy of needs, then the model won't be able to help them, and could lead to them not feeling heard, or to them being misled.

The second view does not dare to posit what someone's desires and needs are, let alone offer advice on how to fulfil said desires. It instead assumes that everyone is entirely different, and so each person must be the ultimate authority on themselves, as no one else has any knowledge from their own experiences that can be applied to the individual. This second view also has limitations, because any kind of guidance or insight from an expert is sacrificed to the fullest appreciation of the individual's individuality. In such a situation, where no comparable experience is possible as each person is infinitely different, only the client can help themselves, and the expert merely facilitates where they can. Whilst facilitation is a very useful skill, an expert is severely restricted if they are unable to offer their own insights to help a client.

There is, however, a third view, and this is the one the stems from a Type theory of personality differences, i.e. that there ARE differences between people BUT the most salient differences are predictable and generalisable in some way. With such a view, an expert can give their insights and advice, because they understand what the client may need based on comparable experiences. At the same time, the expert won't give generic advice because they accept that different people need different things, and will instead tailor their advice to what they know of the client's type.

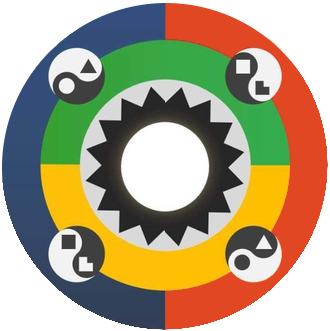

Eight Elements:

Pragmatism (Te), Emotions (Fe).

Eight Functions:

Leading (1), Creative (2),

Vulnerable (4), Role (3)

Mobilising (6), Suggestive (5),

Ignoring (7), Demonstrative (8).

Sixteen Types:

Reason 2: Type theories enable narrative-formation

There is no doubt that the best example of a Trait Theory, the Five Factor Model, a.k.a. the Big Five, is a scientifically exemplary model of personality, using exploratory factor analysis to find that the words we use for personality naturally cluster into five groups. It certainly has its uses and is the best model for those uses, such as measuring the variances in personality traits across large numbers of people, and using this to conduct scientific research.

However, when using the Big Five for different purposes, such as coaching or dating, the Trait Theory comes up short. Being told by an expert that they have 49th%ile Extraversion and 61st%ile Agreeableness can tell a client something about how they differ (or don't differ so much) from the rest of the population, and that's where the value comes to an end. When asked "What do I do with this information?" the science has no answer. A disingenuous expert could say that the person needs to work to 'balance' themselves out, or they could say that the person needs to 'play to their strengths', but neither of these conclusions follow from the mere measuring of behavioural variance. Being low in Extroversion doesn't mean a client necessarily has any kind of skillset to capitalise on. It certainly will not tell us if the client wants to be this low in Extroversion, or actually sees it as a hindrance, and the Big Five cannot say if it is a hindrance or not. If a client is 50th %ile in everything, very little can be said about them at all. Similarly, said expert would have no good answer to the question "What sorts of people should I build a team with?", as the Big Five tells us nothing about how different amounts of different personality traits clash or complement.

Our societal shift towards positivism, i.e. the belief that only that which can be scientifically verified or logically proven is meaningful, has come at a significant cost, leaving many without a justifiable sense of meaning or purpose in their lives, as the traditional sources of meaning, such as culture or religion, are no longer deemed valid. It is arguable that such a shift has led to an unprecedented rise in mental health issues. In a similar way, as shown above, we are unable to build a meaningful narrative out of percentiles of personality traits.

In contrast, with more advanced type theories, such as Socionics, a personality type includes a series of concepts that bring meaning, including the following:

- A dominant lens that shapes a person's attitudes

- An impressionable area of need that seeks satisfaction from others

- An aspirational driver that leads a person to overconfidence and a fall

- A reluctant coping mechanism that brings feelings of dissociation.

From such concepts, a personal narrative can be built, with a clear path for personal growth and development, with warning signs of how a person can stray into activities that are not in their best interests. In addition, mapping of these concepts for one type onto another type creates unique but describable dynamics that can be analysed to determine what relationships complement and what relationships clash. This can help a client understand, not only WHAT they need to work on in their lives to feel fulfilled, but also WHO they need to help them on their journey.